The Generalist Breakthrough: Why Universal Robots Succeed Where Specialized Machines Failed

Executive Summary

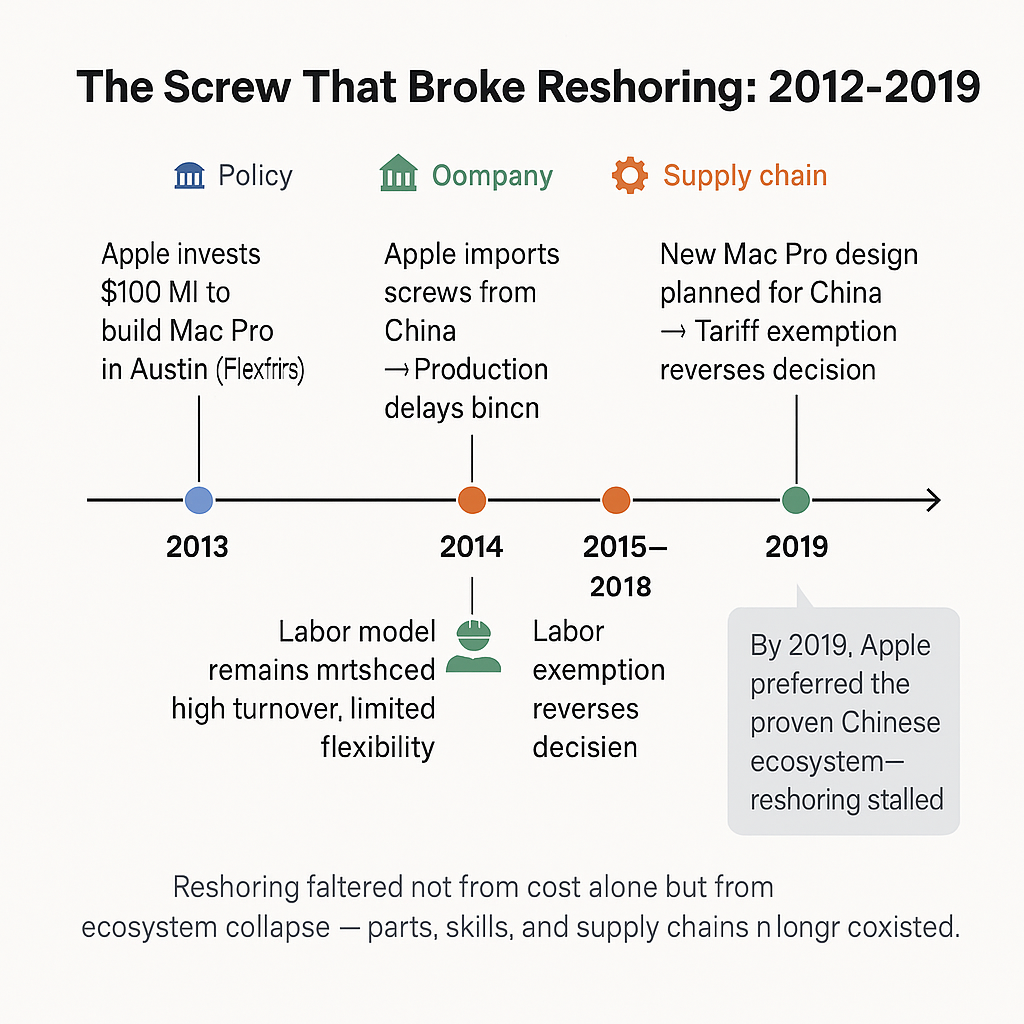

America’s 2010s reshoring push failed not for lack of money or machinery, but because specialization trapped labor, parts, and knowledge in place. Apple’s Austin factory exposed the collapse of that ecosystem—machines ready, supply chains missing, skills outdated.

Universal robots promise to break that lock. Powered by Vision-Language-Action (VLA) models, they merge seeing, reasoning, and movement, switching tasks in hours instead of months. Flexibility replaces precision as the new industrial currency.

They won’t fit every factory, but in volatile, high-variety production, adaptability now outweighs optimization. Manufacturing’s future isn’t about bringing factories home—it’s about making factories move.

The reshoring dream of the 2010s failed not because labor was too expensive, but because labor was locked in place—by machines that couldn't adapt, supply chains that couldn't move, and skills that couldn't transfer. The universal robot is the key that unlocks all three.

The Screw That Broke Reshoring

When President Obama unveiled his manufacturing renaissance in 2012, the government allocated billions of dollars through programs like the Advanced Manufacturing Partnership. What policymakers didn't account for was that machines alone cannot manufacture products. They require two other ingredients that money cannot instantly conjure: a functioning supply chain and workers who know how to use them.

Apple's 2013 attempt to build Mac Pros in Austin, Texas became the cautionary tale. The company invested over $100 million and assembled a team at a Flextronics facility. Six months in, the project hit a wall that had nothing to do with technology or capital.

It was a screw—a single, custom-designed fastener.

The local supplier Apple found could produce about 1,000 screws a day—an order of magnitude off what Apple needed. For a company planning to ship tens of thousands of units monthly, the arithmetic was brutal. Even at a conservative production target of 1,000 Mac Pros daily—each requiring just 10 screws—the demand would hit 10,000 screws per day.

The Texas supplier had deliberately exited mass production years earlier, unable to compete with Chinese manufacturers. As the owner later told reporters: "It's very difficult to invest in the U.S. for that kind of order because you can get it very cheaply overseas." He'd replaced his stamping equipment with precision machines suited for small-batch, high-margin work. Apple needed scale. Texas offered craft.

When Apple finally secured a second supplier—Caldwell Manufacturing—the logistics turned personal. Late one night in December 2013, a Caldwell owner loaded 5,000 custom screws into his Lexus and drove them to the Flextronics plant. The order of 28,000 screws ultimately arrived in 22 separate deliveries—the kind of improvisation that works for prototypes but collapses under production volume.

The screw shortage delayed Mac Pro shipments for months. Customers who ordered on launch day in December 2013 received delivery estimates pushed into 2014. Eventually, Apple gave up and imported the screws from China, undermining the entire "Made in America" narrative before the first full production run.